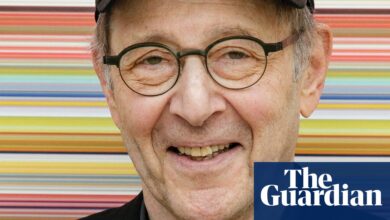

Sofia Jobeolina is obituary Classic music

When the composer Sofia Jubolina, who died at the age of 93, has begun public ideas in the music of the concert, it has proven a provocative step to take the Soviet Union in Leonid Brinv in the late 1960s. These ideas were expressed through titles and a kind of drama that she described “useful symbolism”. Switching from one tool to another, or between different parts of the same tool, she suggested non -musical and non -theological ideas, but rather the equivalent of the vocal for engineering and symbolic deformities familiar to the Eastern Orthodox Church icons that she loved a lot.

With works like introduction (1978) by Piano and the Orangetra of the Car In a cross (1979) for the Chilo and the member, She gained a good reputation in the world of informal Soviet culture, and it is inspiring for its lovers, but it irritates the ancient guards of the Union of composers. She refused to scare.

The violinist Gidron Kremir Concerto Offertorium (1980) To the orchestra outside, Gubaidulina music began to appear at concerts and festivals around the world. I followed the commissions, like Allellia (1990), for the Philharmonic Berlin Orchestra and the vocal forces conducted by Simon Ratal; the Viola Concerto (1996), for Yuri Basmet and Chicago Symphony Orchestra; Also, Concerto In Tempus Praesens (2007), for Anne-Sophie Must.

In 1992, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, Jubidolina moved to Ibn, a village outside Hamburg, in Germany, seeking peace and calm that seemed to have moved from Moscow. There she spent the last three decades of her life, consisting in each mediator, from her vast Oratorios to the smallest pieces of a single dual voice or unaccompanied sound. As she is old, her deep and emotional Sufism, rooted in her religious convictions with enthusiasm, has become more focused and wasted at the end of history and the world.

However, in every piece it always seemed to start again. She was pleased to treat every new day of her life as an opportunity to search for something new and unimportant and she was never afraid of technical risks, as is the case with Under the tree (1998) For Japanese individual tools and orchestra, and God’s wrath (2019), for the orchestra.

Gubaidulina music reflects and embodies it for lifetime for artistic freedom: not just the freedom of composers in writing what they write, but the freedom of shows is to play what they hear (“in joy”, as she used to put it, with a childish smile), and the freedom of every listener to hear what they hear, and they are not what one of them said to listen to them.

He was born in Cesisopol in the Tatar Republic of the Soviet Union, in the middle of the road between Moscow and Kazakhstan, Sofia was the three youngest sisters. I grew up in the capital of the Tatars in Kazan, on the Volga River. Her mother, Vidusia (Ni Lakhfa), was a teacher of mixed Russian heritage, her father, Jobidoline, the land surveyor, from the Tatar family. Both were strong supporters of the Communist regime and Soviet values.

Sofia was especially dedicated to her father, although he could not accept her choice of job or her religious beliefs. I remembered him quietly in Tattar’s language with his friends (never learned it, as the family was speaking Russian), and accompanying him in the countryside in his work where his long silence, “teach me how to listen.”

Gubaidulina sisters were the elderly musician and there was a big piano at home. When she started her own lessons, she made a rapid progress. I hated the “poor pieces of pieces” that I gave to the study, which quickly taught themselves to improvise, a skill that remained of the importance of life; The relief came when her teacher came to Bach, Mozart and Beethoven.

The family was atheist, but although it was still small, it saw an icon in a person’s house – “I got to know God.” She was proud that her father, the father, Massagud Jopolin, was God, and that she kept her office a picture of him in a turban, although she had no memories of his interview.

After five years of university studies at the Kazan Institute, in 1954 she moved to the graduate study course at the Chicovsky Institute in Moscow, where its teachers were among Nikolai Pico and Veron Shipplan, both of whom are unusual.

On one occasion, when someone publicly criticized her “wrong path”, another, Dmitry Shostakovic, quietly told her “to continue your wrong way.” It was accepted in the Federation of Soviet composers in 1961 and graduate studies ended after two years.

At the end of the tail of the melting of Khrushchev, Moscow was a boiler of new artistic ideas. With its contemporaries, who included composers Alfred Shanakki, Arvo Bert, from Estonia, and Valentine Selfistov, from Ukraine, she was fascinated by everything that her hands could put from the world in which you will find everything beyond that, but we will find everything beyond that, but we will find everything that ignores it. Something ourselves hungry. “

The most inspired by her confrontations with European religious music of various types, and its first impressions of modernity in the twentieth century, whether in the form of Weberne, Berge, Traininsky, or the “length” generation later from Carhhins Stokehausen, Luigi Nuno, Ianis Zenakis. Through a friend, I also discovered the various original tools and sounds of cultures, especially those in the far east of the Soviet Union. Even from an early age, there were hints of what would have come: a certain purity of sound and preaching the talisman of euphoria.

The Soviet Union supported a huge film industry, which provided job opportunities for the two composers. Gubaidulina’s production of film music was a prolific production. I worked at a tremendous speed, noting: “I write film music for six months, take a month to restore my health and then write my own music for the rest of the year.” Although it has recorded many types of films, ranging from adolescence Chuchilo (Scarecrow, 1984) to The cat that walked itself (1988), she was particularly proud of her music for children’s cartoons.

Film music was not subject to the same political controls, such as concert music and popular music, and proved to be a good place to experience and learn discipline.

“It could make the deepest darkness shine with the brightness of light!” I noticed her cheerleader. The same can be said about the music that found her distinctive voice. I met her for the first time after her arrival as a graduate student in Moscow in 1984, at an electronic concert where for her Vivente – Chair Vivente (Surrounded and dead, 1970) was played. It was open and warm immediately.

In 1956, she married Mark Lando, a geological scientist and poet, and they had a daughter, Nadiza. Marriage of divorce, as the second did, ended to the Sufi and the dissident Nikolai, later Nicholas, Bokov. In the nineties of the last century, she got married to the pianist and perspective, Pyoter Mishannov. He died in 2006; Nadiza died two years ago. Jubolina survived by two grandchildren.