University art historian solves a 70 -year -old puzzle behind the theft of the famous image

The artwork was stolen by the famous Flemish painter Anthony van Dyck from a luxury house 70 years ago – because the thief wanted to buy new curtains, as a historian claimed.

The surrounding mystery was resolved by stealing the original oil drawing in Northhamptonchier, according to Dr. Meridith Hill from the University of Exter.

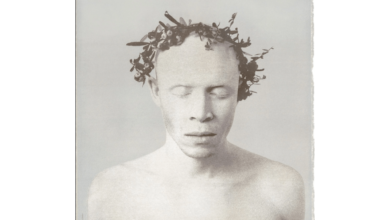

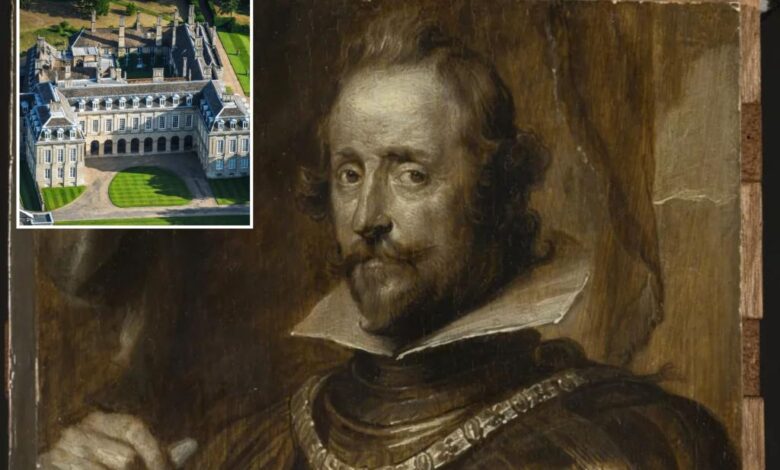

The Wolfgang Wilhelm image of Pfalz-NeuBurg, part of a group of 37 drawings of oil in the seventeenth century, was stolen in 1951 from BUNGHTON House, the Duke of Buclyuch and Queensbery in Northamptonshire, which was residing in 1682.

Her disappearance was discovered after only six years, when Marie Montagu Douglas Scott, Duchess of Buccliocy and Queenzbury, visited a Harvard University exhibition and saw the featured drawing.

Now, thanks to the investigation conducted by Dr. Hill, a great lecturer in the history of art and visual culture, the story of how artwork works across the Atlantic Ocean, through some of the most prominent members of the artistic institution in the United Kingdom and the United States of America.

Dr. Hill spent a year to sift correspondence from all major parties – including Christie’s auction house – to create a significant accurate schedule when her hands changed and the inquiries that followed to prove their source.

The artwork has now been returned to its legal owners, and the story of their pursuit of the truth has been listed in a new paper in the British Art Journal.

Dr. Hill said: “Through new archival research in the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada, I managed to rebuild the plate’s movements for three generations, as it went through the hands of experts, governors, auctions, merchants and gathering from London to Toronto.

“These sources do not reveal a dynamic image of events only because they reveal, but they highlight the factors that contributed to the success of the theft, above all, including the conceptual and material complexity of the Van Dyck icon project and the boldness of the thief in respecting experience.”

Dr. Hill says that this thief was Leonard Gerald Ramsey, the magazine’s editor, The Konoiser, and a colleague of the Archeology Association.

In July 1951, Ramzi visited Ramzi with a photographer, to collect materials for seven pages of the magazine’s book in 1952.

Among the many things that were there to save during the war, 37 wooden paintings of the innovative icon project in Van Dyck were.

Each painting included a drawing of an oily paint for a prince, researcher, military leader, or a prominent artist, and was used to create publications for sale.

Dr. Hill said that the Wolfgang Wilhelm drawing was the last time in Boughton in July 1950, and was located near the door of a small storage room, making it “perhaps the easiest kidnapping”, as suggested by Sir Oliver Milar, deputy surveyor in the royal group.

Correspondence between Ramsey and the art historian Ludwig Goldsider revealed that the first was planning to sell two paintings because he needed money to buy new curtains.

As a result, Goldscheider presented a certificate of authentication, which accompanied the Wolfgang Wilhelm image when it was unknown in Christie’s for 189 pounds in April 1954.

Dr. Hill followed the sale of the image less than a year to a technical merchant in New York, before moving to a second dealer by March 1955, which was cleaned and calmed.

Then it was sold to a private mosque, Dr. Lillian Malikov for 2700 dollars, and her role in turn donated him to the Harvard Art Regiment Museum.

In her research, Dr. Hill repeated the increasing correspondence between the coach of the museum, Professor John Collidge, and Ramsay, as the former tried to create a source of the image by just raising fears by the Duchess.

Ramsey claimed that he bought the image from a market in Hemil Himbstide, and also tried to suspects the authenticity of the image – something he was supported by Goldsider when he contradicts the previous certificate of approval.

With the growth of suspicions, the museum returned the picture to Malikov in 1960, and at her death in 1981, it was donated to the Museum of Art at the University of Toronto.

Dr. Hill said: “As it becomes clear from the research presented here, we were finally able to solve the issue of whether this is the stolen image of Beedton.

Thus, the Executive Committee of the University of Toronto voted on Deaccession on the image of Wolfgang Wilhelm from PFALZ-NeuBurg and returned it to the Bucleuch-73 years after its stole. “

The investigation was conducted as part of Leverrosi Fellowship Research in a group of Van Dyck paintings in Bugon, where Dr. Hill was wandering in the Bougon House archive, the archives of the Paul Mellon Center in London, and the archives of the J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, the Fujg Museum, Harvard University.

Dr. Hill added: “This is an important case because this was a terrible violation of confidence by Ramzi – basic confidence for scientists working in this field, and museums and libraries that carry these invaluable things and antiques.

“Moreover, this was not just a single artwork, but it is part of a unique set of works remaining in the Van Dyck Studio at his death in 1641.

“Without this painting, Boughton Oil graphics were like the puzzle that was missing into a central piece.

Theft and restoration of Grisaille by Anthony Van Dyck (1599-1641): A picture of Pfalz-NeuBurg was published in the latest version of the British Art Journal.