The Age of Fantasy: Competing Visions, Colliding Worlds

Last July, renowned English literature professor Karen Swallow Pryor answered this question Political article Examination of the Nomination of Vice Presidential Nominee J.D. Vance by J.R.R. Tolkien Lord of the Rings (LOTR) as a leading influence on his political views. She announced the news that “The rise of the fantasy generation,” thanks to Vance’s status as a millennial — someone who came of age during the advent of Peter Jackson’s blockbuster film trilogy based on Tolkien’s books.

I, too, have found that my personal and political views are drawn heavily from fictional literature via an entirely different body of work: the comic book.

In her article, Dr. Pryor gently points out that the way you read Tolkien’s work within the binary framework of good versus evil, and link it to a representative of the Trump campaign’s MAGA slogans, is a misappropriation of Tolkien’s work that he himself would have rejected. She emphasized that to love a good book, you must interpret its message carefully, and that the interpretive keys to doing this are time and experience. She implies that Vance’s reading of Tolkien’s work could benefit from more of both.

At this point, the GenX reader let out a deep, sad sigh.

A love of fantasy literature may be a hallmark of membership in the Millennial generation, but a hallmark of membership in GenX is a disregard for our experiences. My own life experiences have an extraordinary number of similarities to Vance’s—a childhood shaped by abuse, profound family dysfunction, and a path to a more economically and situationally stable life paved by academic scholarship and a career in Silicon Valley. I, too, have found that my personal and political views are greatly influenced by fantasy literature by a very different body of work — one with a much longer history, and a multimedia franchise whose pop culture and economic impact exceeds even the LOTR film series by a long shot. Order of magnitude. However, out of respect for Dr. Pryor, the type he is based on is not one she likely spent a lot of time with.

It’s the comic book.

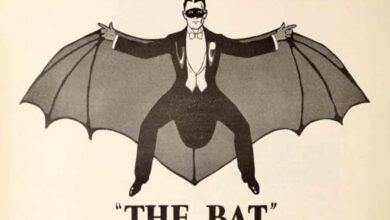

Comic books first rose in popularity before World War II, long before that Lord of the RingsIt was published in 1954. The serialized short stories center on “superheroes” from other universes, and are told through dynamic artwork, speech bubbles, and action sequences filled with voiceovers. Picture books have long been recognized as a more accessible (and more popular) form of storytelling for younger or struggling readers, and are therefore the target of skepticism by parents and teachers as to their true literary value.

My personal introduction to the world of comic book characters came through its oldest and most beloved hero: Superman. Born on the planet Krypton and sent to Earth by his parents to escape the destruction of his planet, Superman grows into a man with superhuman abilities (powered by Earth’s yellow sun) such as flight, and superhuman levels of virtue, all disguised behind a pair of glasses and a desk job at a local newspaper. I first encountered and fell in love with Superman through TV reruns of the black-and-white TV series from the 1950s, then through comic book anthologies I found at the library. Then came Super Friends, the Saturday morning animated series that introduced me to Superman’s allies in the pursuit of truth, justice, and the American way — characters like Wonder Woman, the Wonder Twins, and AquaMan.

Lewis…coined the phrase “true myth” to describe the story of Jesus, because it has all the characteristics that make fiction fictional.

If I had been old enough to have seen the first Superman movies when they came out in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I wouldn’t have been allowed to; Going to the theater was forbidden in my house. But that ban backfired in a big way when I watched them on VHS during a middle school sleepover several years later. My teenage daughter didn’t notice the palpable chemistry between Christopher Reeve’s Superman and Margot Kidder’s Lois Lane so much as she absorbed it straight through my teenage pores.

The degree to which my upbringing in Christian fundamentalism was closely intertwined with my experiences with childhood trauma and neglect should have served to inoculate me spiritually against faith of any kind. However, thanks to what can only be described as a series of divinely directed circumstantial disruptions during my first year of college, I became a Christian a few months before my nineteenth birthday.

It was Tolkien’s friend and contemporary C.S. Lewis who coined the phrase “A true legend“To describe the story of Jesus, because it has all the characteristics that make fiction fantastic—the existence of a world beyond what we can see, a power beyond what we naturally possess, a cosmic battle between good and evil, and a heroic savior. Who saves us and calls us to victorious battle with Him. The additional and essential characteristic is that for… For Lewis as for me, this is all quite true.

As I moved to college and into adulthood, the more my story became intertwined with the true mythological story of the Bible, the more I learned to appreciate the other myths it echoed.

And so it was when I watched it for the first time Lord of the Rings Triple.

I was thirty years old, married and a mother of two young daughters, and beginning the second decade of my spiritual journey as a Christian. I wasn’t familiar with the book the films were based on, as I picked it up and put it down more than once during my high school and college years. Watching the movies aroused in me every inclination to try reading the book again. All the themes were there: the call to something beyond yourself, the reality of evil and the determination for the triumph of good, the need for a sacrificial savior, and so on. Peter Jackson captured Tolkien’s vision and characters to a remarkable degree, and he had the box office receipts to prove it. However, even my third attempt to read the book after watching the films failed. There was something about Tolkien’s world that seemed too far removed from my own to draw me fully in.

Then came the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

Having grown up with Superman and the characters of the DC universe, I was initially unfamiliar with the characters of the rival Marvel Comics universe. My enjoyment of the first two films – Iron Man and its sequel – had as much to do with the redemptive story of the actor playing them as it did with the story itself. I skipped the later story of Thor. I was skeptical and confused about the character connections and the plot which seemed like a rip-off of Norse mythology.

The fantasy world imagined by Stan Lee provided a more compelling mythological lens through which to interpret my vision, compared to the world imagined by Tolkien.

But then came Captain America, a Platonic ideal reinterpretation of the true Jesus myth as you’ve seen it before, about a man born in weakness and given supernatural power to save others, who sacrifices his life so the world can be saved. Then came Avengers, the first film to bring together the stories of Iron Man, Thor, Captain America and a host of other characters in one film, each bringing their backstories and powers together in one collective quest to defeat the forces of evil. Once and for all (or even the infamous post-credits bonus scene that indicated another twist was around the corner). And I was hooked.

Over the next 15 years, the complex timeline of 34 films and 24 streaming MCU series threaded itself across the timeline and milestones of my life. Only now, as I enter my fifties, am I able to look back and understand why the fantasy world imagined by Stan Lee provided a more compelling mythological lens through which to interpret my theory than the world Tolkien imagined.

While Tolkien’s story is set in the fictional Middle-earth, the stories of the Marvel Cinematic Universe keep one of its characters firmly planted on the ground, between real places (New York, Oakland, and the New Jersey suburbs) and the real events of Earth. With others in imaginary worlds.

In the fantasy world of LOTR, power is property, and not everyone has the same ability to use it, let alone contain it. In the MCU, power is inherent in existence, and all living things possess it to some degree. Our powers of the Force can be changed in an instant – not only externally by purchasing a set of magic stones, or by wielding a magic hammer, but also internally, thanks to the explosion of a lethal weapon created by your own company. Or an electronic injection of life rays, or the bite of an experimentally modified spider. It is our inner motivations and choices about what we do with the power we possess – individually and collectively – that determine the kind of person we become, and our impact on the world, whether we are human or superhuman, animal or robot. male or female.

In the real world, we are all born helpless, and not all of us are helped through the difficult path to adulthood in the ways we need. For those of us born into the dark company of childhood trauma and neglect, like J.D. Vance and I, fantasy literature offers a window into a world that soothes the darkness of the past and present, but it also invites us to believe that the future is better. It is possible, and we can have a role to play in making it happen. This invitation is especially attractive when we see ourselves in the characters making this future a reality.

As a 30-year-old mother, there were no direct entry points into Tolkien’s story for me, or my daughters—literally, no Fellowship membership.

It’s easy to see how teenage JD saw himself in the main characters Fellowship of the Ring– As he was the young man, and the adult man he aspired to be. With the flames burning in the destroyed twin towers of the World Trade Center It is still days away from being extinguished When the first film came out, it was easy to imagine how terrifying and expansive the world it was moving into was. With the release of the third film, months after he enlisted in the Marines, it’s easy to see how the role he envisioned for himself in fighting the forces of darkness has evolved.

But my point of view was different. As a 30-year-old mother, there were no direct entry points into Tolkien’s story for me, or for my daughters – literally no Fellowship membership. Although the few female characters present were always beautiful and noble, they only played a supporting role, never a major role.

Not so with the MCU. From Black Widow and Captain Marvel, to Laura Barton and Peggy Carter, and from Wakanda’s Dora Milaje to Wanda Maximova, the MCU’s many female heroes are active participants in quests and teamfights, as well as appearing in entire stories of their own. . Just as importantly, their characters regularly grapple with the moral calculus associated with the intersection of their powers and responsibilities, in much the same way that their male superhero counterparts do. Some of the most compelling and popular storylines were those like WandaVisionThose that explore characters’ sorrows and defeats, not just their victories.

The MCU’s democratic vision extends to its resistance against archetypes and its intentional incorporation of moral complexity into its stories and characters, which is why I believe that, as a collection of fictional stories, it comes closest to approximating the complexities of real, real-life people. Situations that occur in our real world in the 21st century, as Dr. Pryor advocates.

However, the political battle that is the 2024 election season continues. The bigger question is how J.D. Vance saw himself in the LOTR story as a younger man. nowwho recently turned 40, a husband and father, received just 270 Electoral College votes from the nation’s second-highest office. The Politico article depicts him as a very young Gandalf. Perhaps he sees himself as Faramir, with Osha as Eowyn, given her resignation from her prestigious law firm to join him on the campaign trail.

Meanwhile, Kamala Harris chose Minnesota Governor Tim Walz as her vice presidential nominee. With several decades of age and political and military experience passing on Vance, I couldn’t help but think about Dr. Pryor’s point of view, and wonder what Fales would have thought of Tolkien. Then again, with his father’s Middle American antics dominating the social media atmosphere, maybe we’ll discover that he’s more of a comic book guy.

Time will tell.